MEANING—WHAT EXACTLY?

The lioness and the antelope returned as we left the Tree—un-summoned, as far as I could tell—and lay down to let us mount again. After that, they just seemed to know what was required, bearing us safely back through the surrounding gyre of living things. As I felt the great cat’s muscular back shifting fluidly beneath me, and pressed my hands into the bristled fur of her rhythmically bunching and slackening shoulders, I wondered if these creatures were just pre-programmed features of the place—like automated conveyer cars on some carnival ride. She didn’t feel, or sound or smell that way to me. She seemed entirely alive. Her choice to carry rather than maul and devour me felt deliberate—and generous. Despite all rational knowledge to the contrary, I found myself unable to think of her as anything but living and aware.

As we emerged at last from the revolving migratory surge, the lioness lay down in the tall grass to let me off, and I ran my fingers through her fur in silent thanks as I dismounted. She closed her eyes with a satisfied rumble from deep in her throat, and lay panting softly. Her ears twitched, as if to ward off flies I couldn’t see. I inhaled the dusty musk of her, still searching for some flaw in the illusion, and realized, suddenly, how very badly I wanted not to find one. I was not trying to prove her false. I was trying to believe that she was real. It hurt me—almost physically—to suspect she wasn’t. …Why was that? Piper had clearly only asked the question to mock me, and yet, her question mattered: Why should I care so much about things I knew very well could not be real?

She had virtually admitted that all this was just some kind of inexplicable ‘movie’—doubtless ‘replayable’ anytime the right button was pressed. Why did I still feel so wounded by my inability to believe in it? I turned to look up, one last time, at the impossible tower of foliage rising behind me to vanish in the sky, and ached, even now, to know what I might have found there if I’d only been allowed to climb.

My heart’s true desire? Answers to my deepest questions? …Heaven itself?

Or just some huge mechanical projector?

Behind me, Piper had already started off through the rustling, sunlit field, toward the doorway in that other, lesser tree. And…I didn’t want to follow. But the ‘real world’ commanded my return, and I couldn’t bring myself to deny its call. Chasing after her felt like wading upstream against a current drawing every other living thing there to the Tree behind me. Piper had been right. My brain had not found words yet to explain it, but my mute heart could not pretend that whatever it had recognized here wasn’t just as real as, and far more important than, the stupid dinner party calling me away.

When I finally caught up with her, we forged our trail through the high grass side by side in awkward silence for a time. I still wasn’t sure which one of us she was more upset with, as I replayed our conversation in my head, always coming back to where she’d said, even your kind thinks that meaning is as real as data sometimes.

All I’d done since stumbling into her impossible world that morning had been prod and prod at it for evidence of deception, demanding, again and again, to know how any of this could be credibly accepted. Not that anyone of my kind could have blamed me for that.

Still, I had been a teenage boy for several weeks now. Maybe she was right in thinking me obstinate for continuing to cling so fiercely to obviously outmoded assumptions about what is ‘possible.’ As she’d observed, I had not stopped once to wonder what any of it, even my new youthfulness, might mean. …Or, well, once perhaps, back in that tub, but I’d managed to think through very little then beyond the one obvious distraction that had seized my attention so completely.

“So…what does it mean?” I asked softly.

She looked over, seeming startled. “What does what mean?”

I waved vaguely at everything around us. “This place. You said it was your soul—that it defines you. I…feel it, but…I don’t know…what I’m feeling. What does all this mean to you?” She stopped walking, and turned to me, abruptly, as if my question surprised or confused her. “You’re right, okay?” I looked down, embarrassed. “I don’t really care how it’s done. I just…want to know why it hurts this much to leave.” I looked back up at her. “I want to know what I’m hurting about. What is this—that we’re leaving?” I waved almost desperately back toward the Tree. “What does it mean?”

Her eyes began to fill again, making me wonder what I’d said to hurt her now. “It means that what all life wants most, Matthew, is more life,” she replied at last. “Nothing living ever realizes its full potential. No life ends uninterrupted. Nothing is ever as alive as it can imagine being. Life never ceases longing to be more, know more, do more.” Some of the tears that had been gathering in her lashes escaped to streak down her cheeks. “I think you understood this—better than you knew—the night you begged my mother for a second chance at your life.”

I just stared at her in silence.

“I think you’re feeling exactly what this place is made to embody,” she said. “Life’s endless thirst, its inexhaustible beauty and potential, its incalculable worth, its fierce love of other life in all its forms. If there is something beyond life itself, our kind knows nothing of it. We live to live, and to cherish, not just our own lives, but all the life around us. ALL of it, Matthew.” She spread her arms out. “This is our nature.”

“That’s…too big…to help me any. I need to know…what’s this trying to tell me?”

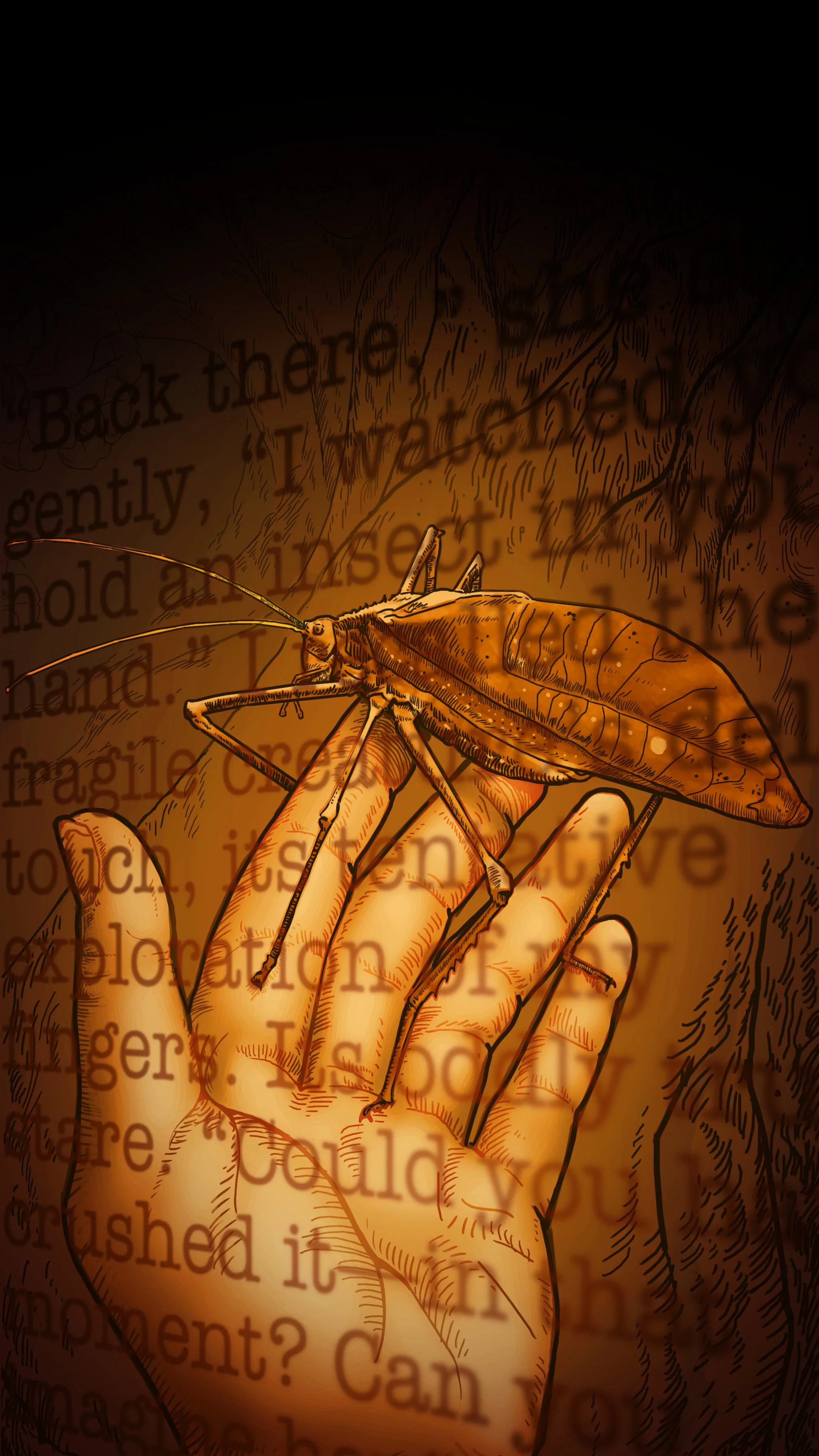

“Back there,” she said gently, “I watched you hold an insect in your hand.” I recalled the fragile creature’s delicate touch, its tentative exploration of my fingers. Its oddly trusting stare. “Could you have crushed it—in that moment? Can you imagine having done so, even now?”

I gaped at her, viscerally repelled by the idea, offended, even, by her mere suggestion that I might have done it. “Of course not! Why would you even think—”

“That is how we feel, Matt. Not just here, so near the Tree, but all the time. We do not end any life, casually—or at all if it can be avoided. Because we feel about all life the way you felt about that insect, and the lion, and all the other animals you’ve just shared this place with.”

I thought suddenly of Rain’s remorse that morning, after saving me back in those tunnels. “That’s why Rain felt so bad about…the man who died while they were chasing us?”

She nodded. “To have played any part in the death of another person—even accidentally… That will haunt him—would haunt any of us—for a very long time.”

“But then…they were your kind too. What would they have done to us?” I asked. “If Rain hadn’t got us both away.”

It was her turn now to look down uncomfortably. “Our kind are not immune to being broken. Some among us…lose themselves in pain, in anger, and despair.” She looked back up at me. “And there are many ways to hurt others very badly without ending their lives. They would not likely have been kind to you—or even to Rain, perhaps. Their way is not ours, Matthew. They have abandoned our way—abandoned themselves. But after being made to suffer badly enough, for long enough…as your kind has so often made us do…some of us fall very, very far from the Tree. The man who died this morning found the end of a path that he, not Rain, had chosen long ago. And still…I think you saw what it did to Rain.”

“Yes. A little, anyway.” I struggled with an urge to apologize, though I couldn’t say what for. I had never guessed her people existed, much less made any of them suffer. Not in any way I’d known about. Still… “Why should any of you want to help me, if it’s our fault somehow that some of you get…broken?”

“You are life—as much as any other,” Piper said, turning to resume our journey toward the doorway. “And you are here, at least in part, because you risked your life for mine. How could we be anything we are, and not want to help you?” She gave me a long, considering look. “You asked me this morning, when we were waiting in the tunnels for Rain’s return, why we couldn’t simply use our powers to make war on you.” She looked away again, and shook her head. “Some of the most broken among us have tried. I won’t deny it. But as a people, Matthew, we could not do so without losing all we are. And to gain what in exchange? What is there to feel but revulsion at the idea of winning a war by becoming the enemy?”

“We’re not all your enemies,” I said. “My kind aren’t immune to being broken either, but no one I have ever known personally wanted war. I’ve never had any desire to hurt anyone.”

“I know,” she said. “That’s obvious. But as a people, war is your way.” She offered me a look of obvious apology. “I’m sorry to say it. But surely you cannot look back on even the sanitized history you’ve been taught, and not see how your kind has always gloried in warfare—from age to age. Your children are taught to hurt others on every so-called ‘playing field.’ They’re trained to feel proud of it—and shamed for any inability to elevate themselves by wounding others. Listen to the very words you use to speak about competing: you beat each other at a game. Their team thrashes yours. Your favored politicians demolish their opponents. I’ve heard your kind congratulate someone who’s succeeding with the phrase, You’re killing it!”

“I get it. You can stop.”

“And now I’m shaming you. Again.” She looked down, seeming stricken. “What on earth is wrong with me?”

“So, are we doing something to your people now?” I asked sullenly. “Or is this all still just ancient grudges being settled?”

“You mean, besides destroying the entire planet?” She glanced back at the plumes of dust thrown up behind us by the gyre of animals our world was ‘through with.’ “Covering the earth in plywood and cement? Poisoning the air and soil and water that everything must live in?”

“So, environmental damage? That’s how we’re oppressing you?”

“Oh, that’s just a place to start,” she said. “There’s so much more, but it’s impossibly complicated, Matthew. Your kind and ours, exchanging wounds, for centuries—each set of betrayals setting the next in motion.”

“History, yes,” I said impatiently. “I got that part too—this morning. But if my people are still doing something to oppress yours now, we don’t know it. How could we? So, what’s to prevent me from doing it again—right here, among you—without even meaning to? I’m not just being nosy, Piper, or trying to pick some kind of fight; I’m trying to avoid stumbling into needless trouble from sheer ignorance. Look how often I’ve upset you—in a single day—without ever meaning to.”

“All right,” she said, “I see your point, and it is wise, but, again… You keep broaching these giant questions as if they could be answered and explained in just a couple sentences. I am not trying to hide the answers from you, Matthew. I just… Imagine someone from another planet walking up and asking you to explain the trouble between…democracies and dictatorships. Or between all your Andinol religions—even just the major ones! If they asked you just to explain your own country’s Civil War, what would you tell them? That it was a quarrel about slavery? That would be true, and woefully misleading, would it not? This is the position you keep putting me—us—in.”

“Okay,” I said, despondently. “But…can’t you just try to…flesh out the big picture for me? Even just a little?”

She fell silent for a while as we walked. “All right,” she said at last. “In a nutshell, as your kind likes to say, here is the problem with you Andinalloi—for my people, and for nearly every other kind of life trying to share this planet with you. Your kind is…relentlessly at work defining everything around you…in ways that leave no room at all for anyone or anything but you.” She looked up at me curiously, uncomfortably. “From your science, to your religions, to your arts and your obsession with money—speaking of empty illusions—you leave the rest of life no ground to stand on. No permission, even, to exist at all. The Andinalloi don’t even leave space for each other anymore.”

She gazed at me, nervously awaiting some response. But I could think of none. At some level, I understood what she was saying instantly. But, she’d been right again; her answer was…too big to enter, much less parse. In some sense I felt she was right, but almost as quickly, a host of objections, questions, challenges and qualifiers rose up inside me. The whole babbling mass of it just left me feeling mute and numb.

“Okay… Thanks for that. I’m going to need some time to…think about it more, I guess.”

“Of course. Of course you will.” She drew a deep breath. “I’m so relieved. I had no idea what you’d think. What you might…say.” She bit her lower lip. “I’m really…quite impressed. You’re being so good about it.”

“For an Andinol, you mean?”

“You keep surprising me.”

“Well…don’t worry. In the ‘surprises’ category, I think you guys are still way ahead.” I tried, but did not quite manage a smile. “So, is my other question any easier to answer?”

“What other question?”

“About whatever ‘use’ Anselm is making of people like me.”

“Oh! Oh, I don’t think… I’m really not the person to discuss that with. Rain will do a much better job of—”

“If I remember right,” I interjected, very tired of getting sandbagged, “you said something down in those tunnels this morning about stealing souls.”

“I also said that was a metaphor,” she replied defensively.

“Okay, so just what is this ‘not exactly soul’ your kind is taking from us?”

“My kind takes nothing from you that the Andinalloi aren’t just wasting anyway. You’ve never even noticed it. Only Anselm’s kind takes…more than that.”

“More than that of what?” I pressed impatiently.

“Ask Rain!” she all but begged. “It’s not my place to have this conversation with you.”

“You said last time that it wasn’t safe to tell me before I’d seen this place. So now I’ve seen it, and I completely get that you guys love all life and would never hurt a fly—except maybe for a couple of you who are broken and confine themselves to torturing us—or stealing our souls, whatever that means metaphorically. I promise not to hold the answers against you or Rain or The Lady, but I want to know what kind of fight I’ve landed in the middle of. And I’m tired of being put off. Is that so unreasonable?”

“Of course not. But—”

“Then what difference can it possibly make which one of you tells me?”

“Rain will know far better how to tell you.”

“He’ll know better how not to tell me. That’s what you really mean, isn’t it?”

“We are not having this argument here,” she said, stalking even faster through the grass. “This is not a place for fighting. I will not defile it this way.”

“Fine,” I growled. “Then I’ll just wait until we’re back through the doorway.”

The rest of our journey was spent in stormy silence. I hardly glanced at the endless line of forest looming over us as we approached the doorway tree, or at the carvings lining every surface of the passage. Just as soon as we had stepped out of the dead tree’s entrance, I said, “Okay, so now we’ve left the temple. You’ve told me lots about who you guys are—which I appreciate—but I think I have a right to know where I am in this story too. I kind of see what my kind’s doing to upset you—now please just tell me what your kind is doing to us because of it, okay?”

She whirled to face me. “You are the rudest boy I’ve ever met! I know now why I keep mistreating you. It’s because you inspire ill treatment! You’re willfully stubborn, and self-absorbed, and deaf to reason, and—”

“—just like you!” I ended for her. “Seems to me that Rain called you more or less all those same things this morning when he found me at your temengeth, or whatever it’s called.”

“Where I only took you to protect you!”

“From WHAT?” I shouted. We stood in silence for a moment, glaring at each other—for all the world just like two teenagers, I realized. So much for ‘Mr. Reasonable.’ “That you’re this determined not to tell me doesn’t make me trust you more,” I said at last. “Any of you, actually. …In case my trust matters.”

“Sit!” she snapped, pointing to a lengthy hump of polished root emerging from the gravel bank behind us. “And I will bow to your commands, Andinol princeling.”

She could call me all the names she wanted, just as long as answers followed. I went obediently to the ad hoc bench, and sat as ordered to.

“I will tell you just as much as I believe my mother’s chancellor might forgive me for admitting to you here—at entirely the wrong moment, in completely the wrong way. When we get back, I’ll go tell Rain what you’ve made me do, and he will stare at me, and stomp around and roll his eyes, and ask me where I left my brains—you’ve seen him do it! You know what he’ll put me through. And I’ll have no defense, since even I suppose the presumptive heir to my mother’s throne really ought to know how to handle one clueless Andinol teenager by now—which my apparent inability to do will just sew further doubt about my suitability to rule at all.” She thrust her chin out at me. “Or—you could just show me a little mercy, and wait one more hour to ask Rain yourself when he comes to get you for the dinner party I am not invited to for having screwed up so many other things already.”

Wow! I thought. Was this what growing up a princess surrounded by nothing but yes-men did for you? Could there really have been forty-seven years of life experience behind that speech? “Well,” I said, “I appreciate your willingness to go through all of that for my sake. I sure won’t forget it. Fire away.”

Her brows lowered in obvious displeasure. “Meaning what, exactly?”

I shrugged. “Meaning, I appreciate your answer all the more now that I understand what it’ll cost you. I’ll let Rain know how much it meant to me when I see him tonight—if that’ll help, Your Highness.”

Her mouth scrunched together like an apple doll’s. She shook her head. “I’ll never feel sorry for you again.”

I gave her a small, tight smile, and waited.