KIDS THESE DAYS

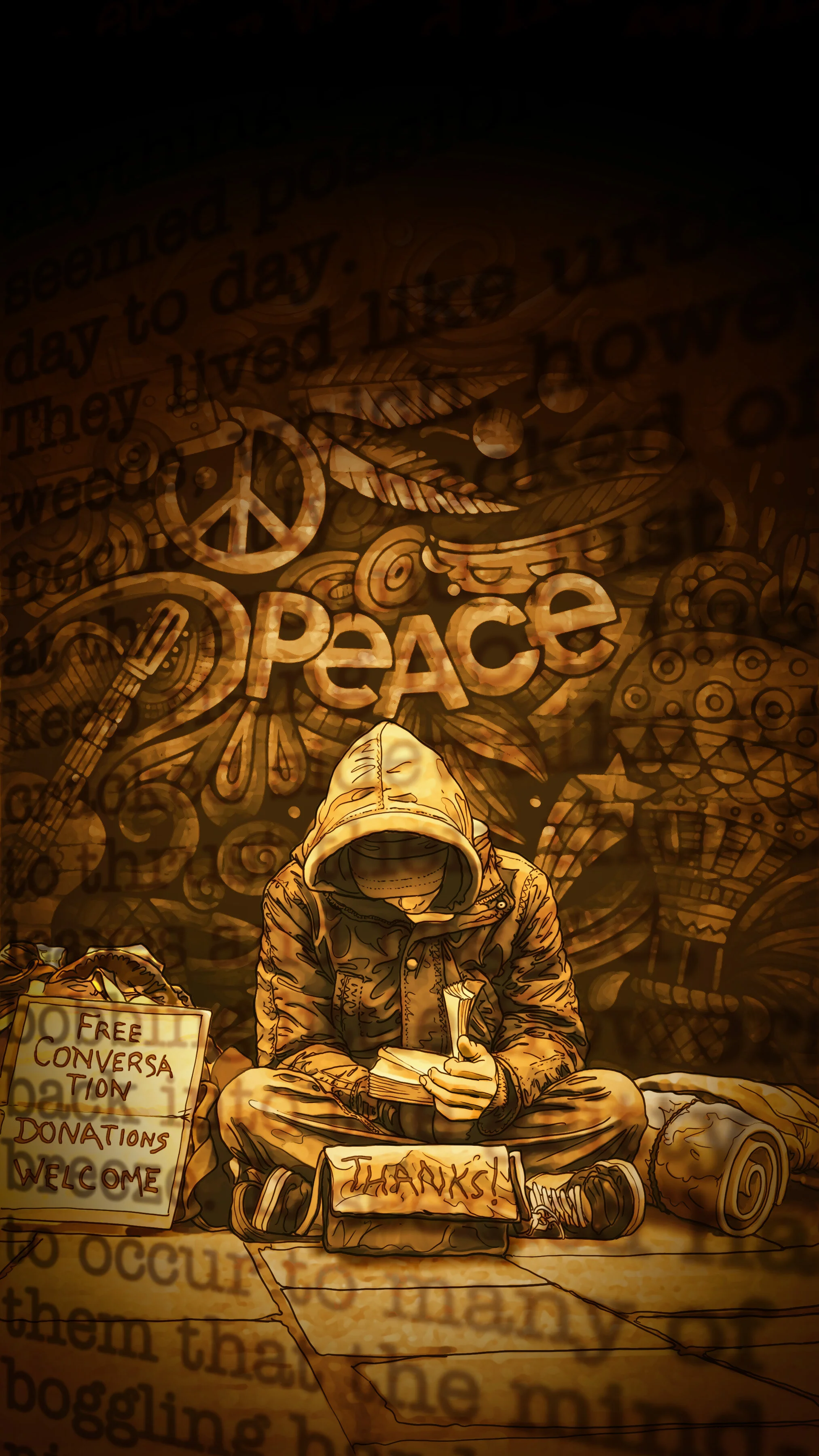

As I spent more time with my new acquaintances on the street, the casual obscenity and grime of their existence became increasingly invisible to me, while both my distress at their brokenness, and my admiration of their practically unconscious courage and endurance swelled. They were astonishing studies in paradox: more vividly and simultaneously light and dark, weak and strong, young and world-weary, vulnerable and dangerous, honest and conniving, theatrical and unaffected, mad and sane than any people I had ever known or dreamed of—an eternally nebulous tribe for whom both anything and nothing seemed possible from day to day.

They lived like urban weeds, which, however frequently hacked off at the ground, just keep rising from the cracked sidewalks again to thrust their thorny leaves and ragged, bobbing little flowers back into the gritty breeze. It seemed hardly to occur to many of them that the mind-boggling hardship and injustice of their lives should be any reason to stop dreaming, laughing, scheming, or inventing ‘something better’ always just around the corner ‘As soon as I get off this shithole street, out of this shithole town, kick this shitty habit. Tomorrow, or next week maybe, or next spring for sure…’ The life inside them, however beleaguered, just didn’t seem to take ‘no’ for an answer.

In other ways, however, their lives seemed to have been forged and shaped by ‘no’ right from the start. Hard up against their inexplicable endurance and capacity for life were the loss and shame, fear, anger and relentless, hounding need that defined them just as deeply. As they became less guarded with me, edgier bits and pieces of their hardscrabble existence began to tumble out.

The lives that had driven them here to start with had left most of them with a great deal of pain to medicate; pain only amplified by the harsh privations of the street. After glancing around for ‘bumble bees,’ as they called the Avenue’s brightly vested street patrol, they’d as often pull out joints now as cigarettes when I was sitting with them. After I’d declined to share their pot a couple times, no one offered anymore—which made me worry they might think I was a narc. But when I finally mentioned this concern to Catcher, he assured me that I seemed a little young to be a cop, and that ‘a snitch,’ as he called it, would never have been so obvious. I was just straight, he said, which, if I didn’t come off all judgmental, would save me more trouble here than it was likely to cause. I remember being struck by the air of weary grief with which that assurance was bestowed, though I didn’t yet begin to understand the reasons for it.

As I passed the days with his unofficial family of ‘younger brothers,’ I came to admire Catcher’s guileless skill at shepherding them through the exigencies of their frenetically motionless lives on the Avenue. Before long, I was seeking them out almost every morning, having learned where and when to look. My abysmal failure at avoiding too-adult language and behavior soon had Catcher convinced that I really was some kind of literal child prodigy. This conviction was embraced by his young protégés as well, who began to badger me with questions about what it was like to be ‘a genius.’ In light of Rain’s warning about not making ‘slip-ups’ even more suspicious by attempting to undo them, I just wove their convenient misapprehension into my vaguely defined back story, careful to frame my ‘freak intelligence’ as an embarrassing obstacle to acceptance from regular people. This approach not only explained away all further lapses, and helped nullify the risks of seeming uppity, but allowed me to openly engage them all as tutors in the art of acting like a ‘normal kid.’

Because of this odd status, I think, Catcher didn’t end up adopting me as another of his fosterlings. Instead, he and I began finding opportunities to hang out alone together and engage in long, introspective conversations of a sort not really thinkable with his boys, or much of anyone else either of us knew there. Gradually, we came to treat each other more and more as equals, even confidants, despite my apparent youth and naiveté. Not until much later did I realize how many of the confidences we exchanged concerned others rather than ourselves. I knew I was hiding, of course. But I was so focused on all he had to teach me about life on the Avenue, and had such a sense of our growing acquaintance as he did so, that I never noticed how well he was hiding too.

Though I never actually saw Catcher indulge in any substance more hardcore than pot, self-administered medications were a staple of daily life around me now. Gathering hints, or sometimes simply risking blatant questions, I started learning how to tell when someone was tripping on speed or E or any of a dozen other substances from cough syrup to acid. I remember hearing Nickel tell Caramel one morning that Toes was “down at Shiver Bridge getting well,” and making a fool of myself—yet again—by asking what she was sick with. Caramel stared at me, then smiled almost maternally and asked where I had come from—no really—where?—before explaining very sweetly that Toes was off “nodding.” Seeing that this just confused me more, she said, with exaggerated patience, “Heroin, Junior Mint. … Toes is a junkie.”

I blinked, trying to conceal my shock. Quiet, sweet, gentle Toes used heroin? “Oh.”

If there’d still been any question in their minds about my being a snitch, I think it must have vanished then. Toes, I would discover soon enough, was not the only kid I knew there who sought refuge in junk from the punishment of being. I learned to recognize their pale complexions slick with sweat, the needle-thinness of their bodies, the long sleeves and pants and scarves they wore, in any weather, to cover up their tracks.

Along with such unwelcome but important knowledge came dawning awareness of what all else they did in my absence to appease their endless need. Beyond the omnipresent ‘spanging,’ as they called bumming spare change, some stole, some scavenged, and some, like Toes, dealt drugs to buy their own. Whisper, however, didn’t want that kind of entanglement with the Mexican mafia from which most of the junk in our fair city apparently came. Nor did she want to feel responsible for leading others down the path that owned her so completely now. So Whisper just sold herself to feed her habit. I discovered all of this one afternoon while I was listening to them debate which of their methods was worse.

“But what’s left, once you give your fucking flesh away?” asked Toes.

“I’m not harming anybody else, at least,” said Whisper. “And the guys I do are mostly nicer than my dad was. They pay for it, at least.”

This casual acknowledgment hit me like a punch in the stomach. I’d read about such things in newspapers, and seen them depicted—by actors—in movies or TV. But Whisper had treated me with kindness and interest from the start, and I’d come to think of her as a friend. As I tried to purge the horrific images her admission had conjured in my head, my eyes began to swim with unshed tears, and I stood up to leave before embarrassing myself.

Every day among these people left me feeling more a fraud. I’d let them think I too was running from some horrific past, hiding the details behind my so-called amnesia. Even those who didn’t buy it had respected my choice to cover up whatever nightmare had driven me here. They all had one of their own. But while their nightmares were real, I was here, accepted and included by them, under false pretenses—which, to my bewilderment, began to feel not just acutely shameful, but lonely and helpless. How had I spent my whole life knowing nothing about what was going on out here? And now that I did, what was there for me to do about it? I was a ‘little kid’—yet old enough inside to understand that this sweet teenage girl was turning tricks with ‘nicer guys than her father had been’ to pay for her escape from the pain. In contrast to things like that, I was fine—except for being forced to watch all this happening around me without any way to intervene, or even look away. This was, for the moment, my only community. But it was harder and harder to bear this front row seat for so many horrors that could not be unseen.

Yet, where else was I to go? The next day, I found Stitch spanging by the supermarket, and sat down beside him for a while. He talked less than most of the other guys, and I’d come to find his fierce silences strangely companionable. We’d been sitting there for maybe fifteen minutes, watching people ignore us as they came and went with bags full of food, when, out of nowhere, Stitch brought up my ‘amnesia,’ and confided that there were a lot of things about his own life before—at home—that he couldn’t remember either. He asked if I thought he might have amnesia too. After faking vague answers to a couple of his questions, I tried to deflect the subject by asking, finally, how he’d gotten his scars; fairly sure by now that Car Talk’s warning that first day had been nothing but comic hyperbole.

As I’d suspected, no punch followed. He just said, “My mom got mad one night when she was drunk, and broke a bottle ’cross my face.”

“Jesus,” I murmured.

“She was real sorry for it, right away,” he said, as if apologizing for her. “We told’em I ran through the sliding door. She even had to break it so they’d believe us, which kinda served her right, huh? But I thought about it that whole week in the hospital, and…I knew she and me was over.” He paused thoughtfully. “She never sent nobody after me, so I guess she knew it too.”

They didn’t tend to tell their stories unless asked to, if even then. Nor did they ask for anybody else’s. But, sooner or later, pieces of their pasts emerged this way, like splinters of old bone rising through the skin above a badly healed wound. I learned of kids raised by grandparents who’d died within months of one another, leaving them to abusive foster homes or just their own devices; parental suicides that had left surviving family too crazy or reamed with guilt to go on living with each other; drug-addicted parents who’d paid such scant attention to their children that their departures had hardly been noticed… The list grew slowly but relentlessly, supplemented by accounts of more current crises. Nearly once a week, it seemed, I’d hear someone talking about who’d been beaten up or raped at some squat or rave, who’d died of peritonitis from some untreated abscess, or of a knife wound after getting too recklessly in someone else’s face.

Then, one day, it was Whisper I found crying on the sidewalk. When I sat down and asked her why, she told me Toes would not be back. They were saying her overdose had been accidental, but Whisper didn’t think so. We cried together then, for a little while, and no one shamed either of us for it. But when we were done, I got up and went to look for Catcher. I needed, badly, to talk with someone I could really talk to—without holding back; something I still couldn’t do with Lita for some reason. Catcher was the only one.

But I couldn’t find him anywhere. Nor could I find anyone who’d seen him, or knew where he might be hanging out. So I decided to go ask Stacy at Nocturnal Lullaby. I knew she was one of Catcher’s few other close friends, because he’d told me so. But I hadn’t been back to see her myself since the day she’d introduced me to Lita. I still worried, a little, that she might be one of them. I really wanted to find Catcher, though, and hoped she might know better than the others had where else I should try looking for him.

I walked into the dimly lit interior of her shop to find it as empty as ever, and Stacy herself nowhere in evidence. I knew by now that Nocturnal Lullaby had been an Avenue landmark for years, so she must be making a living here. But I’d never actually seen anyone walk out with a bag.

“Matthew!” I turned to see her sweep through the back-wall curtain, as impressive in her powdered face and Goth drag as before—although her long straight hair was hennaed red now. She came toward me with a smile. “It’s so nice to see you.”

“Hi,” I said, suddenly ashamed that I hadn’t come by at least briefly before now to thank her. “I uh… I’ve been meaning to thank you for introducing me and Lita.”

“That’s working out then?”

I nodded. “Really well. I’m grateful. To both of you.”

She shrugged. “My part was easy, and from what I hear, Lita thinks very highly of you.”

“Oh. …That’s good to hear.” I wondered if asking about Catcher now would tip her off that thanking her had been an afterthought.

“Is there something else I can do?” she asked when my tongue-tied silence stretched.

“I need to talk with Catcher, but I’ve looked everyplace, and nobody knows where he’s gone. Have you got any ideas where to try?”

She gazed at me a little strangely. “You don’t look happy. Is something wrong, Matt?”

I wasn’t sure how to answer.

“Is it something I can help with?” she pressed gently.

“It’s…Toes. Have you…?”

She looked down sadly, and nodded. “Yes. I have.” She looked back up at me pensively. “Catcher told me about it. Just before he left this morning.”

Left? “For where?”

“I don’t really know. But…I think he’ll be gone a little while. At least a week or two.”

She clearly knew more than she was saying, and was so obviously deciding how much to tell me, which left me feeling oddly wounded. “Why?” I asked. “What’s he doing?”

She just went on looking at me in that calculating way.

“Just tell me. …Please,” I amended less sharply.

“I know you two have become friends,” she said. “He talks about how special you are.” She gave me a slight, sad smile. “He thinks you have a future. And I agree with him. But…”

“Is he coming back?” I asked, beginning to feel angry at being treated like an outsider in regard to someone I’d thought of as my closest friend here.

“Oh! Of course. He always comes back.”

“This is something he does regularly?”

She sighed and rolled her eyes toward the ceiling. “What’s just happened to Toes… Catcher lost someone that way once.” She looked back down at me bleakly. “It hurt him. Very badly. Things like this…touch all that for him.” She walked past me to gaze out through her display window at the busy Avenue. “He cares about people here so deeply. Too much. And, sometimes, he just needs to get away from that.” She looked back at me. “That’s all it is. He’ll be back as soon as he’s dealt with his own demons in his own way.”

“Who did he lose?” I asked, my irritation eclipsed now by concern.

“These aren’t my stories to tell, Matt,” she said softly. “I’m sorry. But when he comes back, tell him about this conversation, and ask him, if you’d like.” Her smile returned. “I’ve got some lovely tea on in the back. Would you like a cup?”

I felt even more bereft now than I had before, and…I just needed someone who seemed equipped at all to be company. “Yes,” I said, quietly. “Thank you.”

“Good.” Her smile widened. “Why don’t you make yourself comfortable over there,” she pointed at the two chairs beside the little table in the corner where she’d read my cards, “and I’ll be right back with a cup for each of us.” She turned and headed back toward the curtained doorway as I went to flop down into the closer chair.

It was absurd, of course, to expect that Catcher would have left me some kind of message before leaving, but…I had grown used to thinking he’d just always be there somewhere. Lita was at work, and honestly, I could not imagine turning to her for…for what? She’d been wonderful to me—all along the way. But there was something…stern behind her care. After all she’d dealt with, I wasn’t likely to find any sympathy there. And why did I need sympathy anyway? Yes, I’d liked Toes a lot. But I’d only known her a couple weeks. So…what was…

And that’s when it finally occurred to me to wonder whether it might be something else that I was grieving. Not just that morning, but on all the other occasions recently when I’d found myself so broken up about the plights of people I was only just getting to know. Things like this touch all that for him… Was that what I was doing? Using the pain in other lives around me to…process something else of my own? And what else might that be?

“Here you are,” Stacy said, cheerfully derailing this train of thought as she came from behind me with two mismatched vintage porcelain cups of steaming tea. She set one in front of me, and carried the other around to set down at her side of the table before settling gracefully into the chair across from mine. The fragrance was part peppermint, but floral too, and spicy. I took a sip too eagerly, and burned my tongue, wincing as I set it down again.

“Sorry!” she said. “Should have warned you; I just brewed it.”

“No worries.”

“So what have you been up to?” Stacy asked, lifting her own cup to blow on it a little.

“Nothing much.” I shrugged. “Just hanging out and meeting people.” From things she’d just said, it sounded like both Catcher and Lita had been talking to her about me. I found it hard to believe she didn’t know what I’d been up to just as well as everyone around here seemed to know everything else. “Lita and I keep talking about getting me hooked up with this Path and Passage program downtown, but someone she thought we should talk with there has been off on vacation, and…I don’t wanna crowd her schedule.”

“She does keep very busy,” Stacy said agreeably. “Have you thought about just going down there on your own? There are buses.”

I shrugged. “Lita…seems to think it would work better if she took me down and introduced me to people she knows…” I made a sort of helpless gesture. “I…don’t want to go against her advice.”

Stacy smiled oddly at her teacup, and said, “Interesting.”

“Interesting?”

“And none of my beeswax,” Stacy said, looking up to smile at me again. “Sorry. I’m the kind of person who has to keep reminding herself not to meddle.”

“To meddle in what?” I pressed pleasantly.

“It would be meddling to tell you,” she replied even more cheerfully.

This whole conversation had been one long poker game. Stacy was clearly a world class dodger. Who are you, really? I wondered. What are you? I couldn’t ask directly, of course. But, if we were going to play these games… “So, how did you end up deciding to do this?” I asked, gesturing vaguely at the shelves of spooky merchandise behind me.

She seemed surprised by my sudden change of direction. “Why did I open the shop?”

“Why this shop? …I mean, it’s not the usual boutique. How did you get interested in…this kind of thing?”

Her brows climbed slightly. “Catcher’s right about you, isn’t he?”

Damn it, I thought wearily. “Yup,” I sighed. “Boy genius. We’ve all got our skeletons here. That’s mine.” What’s yours?

This was reckless. I could see that. Rain would be scowling at me now. But it had been almost a month, and where were those Stbrich boys? How long was I just supposed to wander around on high alert? Sooner or later, it was going to start looking weird if I didn’t start engaging people, right? I clearly needed some broader collection of truly friendable friends. Stacy seemed one of the most interesting people I’d met here, but was she, or wasn’t she a safe candidate?

“Intelligence is not a skeleton!” she said. “It’s a gift!”

“If you say so. No one my age ever seems to think so.”

“You’ve never met any other kid who admired you for being smart?” she asked skeptically. “Never in your life?”

Oh…clever. Maybe this had not been such a good idea. “I…have no idea,” I said uncomfortably. “I still…don’t remember much.”

She gave me a look of knowing resignation. “Right. So…would you like the short answer to your question, or the long one?”

“Oh, the long one, please. I like the long ones.”

She nodded. “That’s what Catcher told me.” She looked around the shop, seeming to gather her thoughts. “I’ve always had…a strong sense of the other worlds.”

“Other worlds?”

“That’s just what I call the parts of this world that most people aren’t aware of. I doubt they’re really other worlds at all. More likely just other plains of this one.”

“So…what’s in these other worlds?”

“Other kinds of knowledge and ability, other kinds of…being.” She shrugged. “What we call magic, basically.”

“Magic,” I said, trying to sound unconvinced. Had I been right to worry?

“Sorry you asked yet?” she chided.

“…No.” What box had I opened here? Was Rain going to kill me for this stupid move? Or would somebody else take care of that before he could? How would a normal person act now? Skeptical, I supposed, but curious as well perhaps? “I just…what kind of magic?”

She shook her head. “I have no idea.”

“What?”

“I don’t know what kind of magic,” she said with audible regret. “I’ve always sensed it there, practically close enough to touch. I can feel it…reaching out to me sometimes, like when I read the tarot cards. But I’ve never figured out how to reach toward it. Sometimes I know things—or just feel them—I have dreams that turn out to be true, though I have no idea how, or what it means.” Her smile became sad. “When I was a little girl, my mother always told me that these things were a gift. And you know what?” She gave me a wry look. “I’d tell her the same thing you just told me. ‘No it’s not. It’s a curse, Mom. Everybody just thinks I’m a weirdo.’” She nodded sadly at me. “And I agreed with them—for the longest time.”

Everything inside of me unclenched. It took effort not to slump down in my chair and sigh out loud. She wasn’t one of them at all. She was just another wacko human ‘psychic!’ Thank the powers! as I’d heard Rain and Piper say so many times.

And then, I instantly despised myself for even thinking the word ‘wacko.’ Who knew better than I did that there really were ‘other things’ around us in the world? Maybe that’s exactly what she’d been aware of all her life. Knowing everything I knew, how had I still just called her wacko after she’d clearly told this story trying to make me feel better about my gift? What a dick I was! “Well…I don’t think you’re a weirdo,” I said quietly. “But, if it’s been that…painful for you, why…surround yourself with it like this?”

“I didn’t say I still agreed with them. What I’ve got—whatever it’s for—I think my mom was right; it is a gift. And it’s my job to figure out how I can use it.” She tilted her head. “But that’s not why I wanted to open this shop.”

“It’s not?”

She shook her head, looking around with a bemused expression. “None of this stuff has much to do with the real otherworlds, I don’t think. Not in any direct way, at least.”

“Then…why?”

She turned back to me, her smile all but gone. “My mother always said my gift was nothing to be ashamed of. But she also told me it was something best not advertised.” Her smile tightened sardonically. “How’s that for a mixed message? ‘Don’t be ashamed, honey, but just don’t let anybody know.’” She fell silent for a moment as her gaze turned inward. “She said I’d got it from my father. That he’d had it too, and what an amazing man he’d been. But he left before I was even born, and every time I asked my mother to tell me more about him, she just got evasive.” Her eyes refocused on me. “So I was never quite sure how to feel about that either.” She leaned back and drew a long, deep breath—exhaling it as if to purge the memories. “I opened Nocturnal Lullaby to attract other people like myself. I wanted to make a place for them to come feel safe, and seen. No mixed messages here. Nobody trying to hide anything they ‘shouldn’t be ashamed of.’” Her mouth quirked back into a smile, slyer than any I had seen her wear before. “I mean this place to be a welcome sign for misfits and children of any age who feel safer in the shadows. Everybody here is complicated, Matthew. But none of us are really weirdoes. We’re just a little less absorbed into the herd than other people—which is another way of saying we’re uniquely gifted. …Are you hearing me?”

I nodded, and thanked her, though I’m sure she’d have been bummed to know that her kind words had only left me that much more ashamed of the life I’d lived, so comfortably ensconced in shallow, judgmental assumptions. I was still not able then to hear the rest of what she was trying to tell me. After a few more pleasantries, I thanked her again for her many kindnesses, finished up my tea, and fled back onto the street.

Heading back to Lita’s room, I wondered whether Catcher would ever tell me about this loss that made him flee the Avenue from time to time. I thought about the sadness hidden behind Stacy’s life as well, trying to absorb the fact that I knew literally no one here whose life was not defined by past pain.

I paused at the last corner before the turn up to Lita’s building, and gazed around at the busy stream of jaunty shoppers, smartly dressed business people, and casually cool university students who filled this place by day, all just as oblivious as I had been once to the invisible war zone they were bustling through on their way to purchase something fun or have a pleasant meal.

This bleak reverie was broken when I noticed someone watching me, it seemed, leaning against a lamppost; short black hair framing an open, good-looking face, baggy, tan-colored pants and a green plaid short-sleeved shirt. He glanced away as soon as I noticed him, but I’d played that game myself. I’d grown used to being ignored here—by everyone but my own kind, at least. So what was this about?

Without another glance in my direction, the boy just ambled off. Maybe he’d been no one. Maybe he’d just been wondering what I’d been standing there staring at. Still…this had been a day chock full of bad news and ill omens. Had I grown too comfortable playing the ‘boy genius?’ Had the mentors I’d come here to wait for failed to show because I’d been attracting too much attention? …Or was paranoia just as big a danger to my ‘invisibility’ around here as careless complacency perhaps?

I scurried back to Lita’s building and spent the rest of that day reading new age treatises, or staring out her window at the street below, hoping to find no one down there looking back up at me, and still trying to sort out the silent tumult turning underneath my rib cage and inside my head. There seemed some kind of message there that just wouldn’t come into focus. I felt like there was something I was supposed to do—just as Stacy had described: something reaching out for me that I couldn’t figure out how to reach back to.

I felt as broken by now as any of the other ‘riffraff’ I had met here. But they weren’t as weak as I was. They were running—even in their sleep sometimes—but they weren’t half as scared of most things as I’d been all my comfortable life. They were mad as hatters, because they knew too many truths that we, the sane, are never asked to name, much less forced to face. But when the going got horrific, these mad hatters just up and dealt with it like we, the sane, cannot—or died…like Toes.

I stood there feeling, once again, like the pretentious little beagle taken under wing by yet another tribe of tolerant wolves. To think I’d once walked streets like these imagining myself better than those scruffy people bumming change. Now…I just wondered what it might take to feel worthier of them.

Of course, there were a few less costly ways to find some of the help so many of us needed there. One of these appeared along the Avenue a couple times each week: a van inhabited by three or four young volunteers, sometimes as pierced and edgily dressed as we were. They’d lift a couple toy wagons full of food and toiletries, clothes and minor medications from the back of their vehicle and pull them down the street, offering whatever was requested to whomever approached them. While this happened, others waited in a little group to talk with someone holding court inside the van itself. That person, I was told, was there to provide counseling about how to access medical treatment or other care and services too complex to be carted out in wagons.

I sometimes watched all this from safely down the Avenue, leery of anything that might bring me to the attention of ‘authorities.’ I’d been assured that these guys were safe. But those who told me so had no idea what I was hiding, or who from. I did notice, though, that the person offering counsel from the back of that van was often a very pretty young woman, dressed, like her colleagues, in worn, unpretentious clothes, with dark, glossy, curling hair that tumbled halfway down her back. She radiated cheerful generosity. Even from a distance, I could tell she knew the people she was talking to—even liked a lot of them, it seemed, and clearly cared about what they were saying. I was tempted to go meet her too, but knew I didn’t dare. Nonetheless, I did find out from Gummy that her name was Anna.